Building Containers from Scratch (Part 1)

The Foundation - chroot and Filesystem Isolation

Table of Contents

1 Introduction

My learning method follows a similar path most of the time. First, I start using the technology and learn my way into it. Once I feel comfortable, I try to recreate this technology myself. Not necessarily in the same way—my goal isn't to create something production-ready or at the same level of maturity as the original technology. But I focus on the building blocks that make this technology what it is.

In this blog series, I will demonstrate how to build containers from scratch using nothing but Linux primitives. No Docker, no Podman, no container runtimes. Just raw system calls and command-line tools. The goal is to understand what actually happens under the hood when you type docker run.

By the end of this series, you will have built:

- A filesystem-isolated environment using

chroot - Network isolation using network namespaces (

ip netns) - Resource limits using cgroups

- Multi-layered filesystems using OverlayFS

- Bridge networking connecting multiple containers

This is Part 1: The Foundation. We start with the oldest and simplest container primitive: chroot.

2 Understanding chroot

chroot — short for "change root" — is the simplest form of filesystem isolation in Linux. It has been around since the early days of Unix (Version 7, 1979), making it one of the oldest isolation mechanisms available.

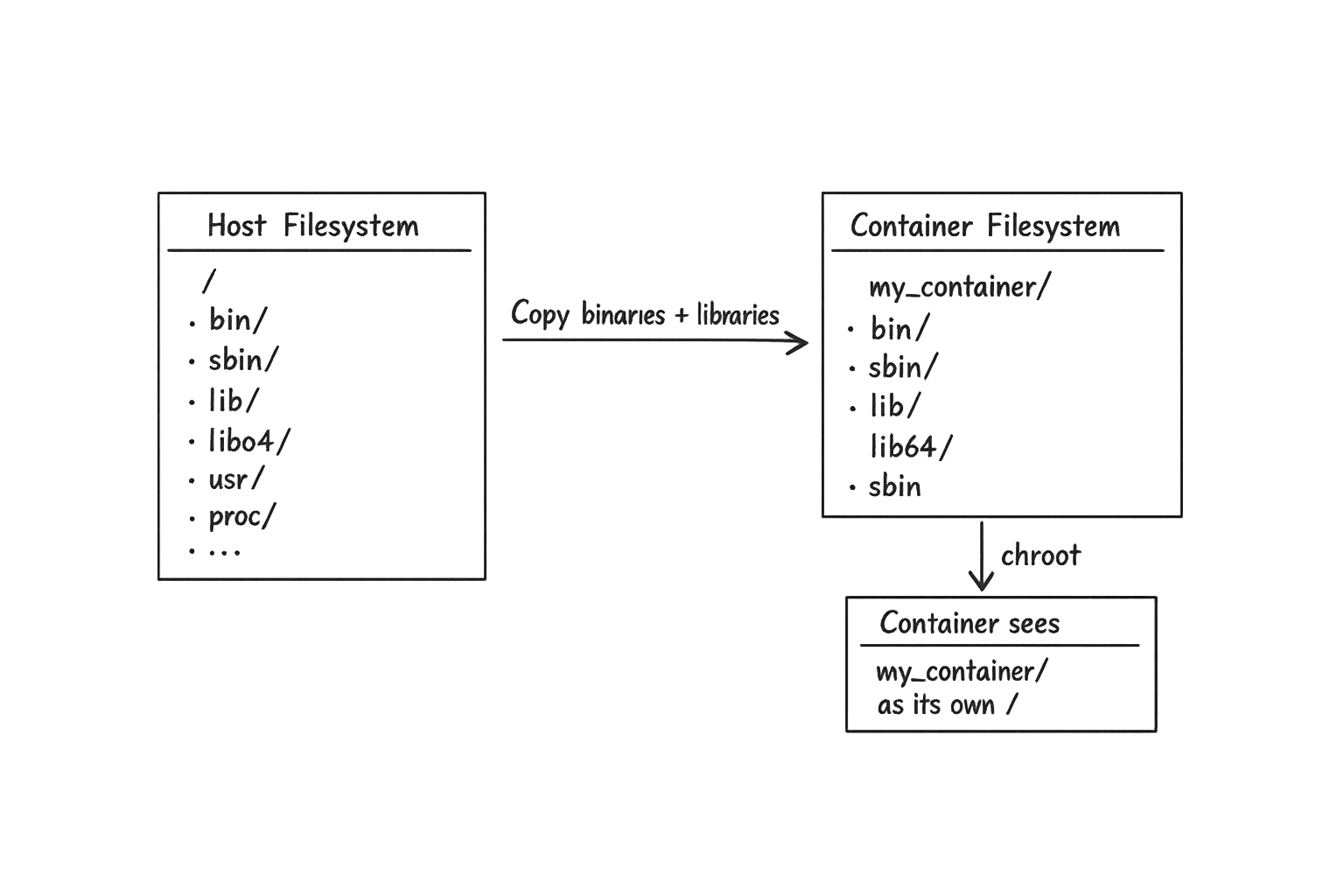

The idea simply is: chroot changes the root directory (/) for a process and all its children. Once a process is inside a chroot, every path it resolves starts from this new root. It literally cannot reference anything above it in the directory tree.

How It Works

The process inside the chroot cannot see anything outside its new root. This is the foundation of filesystem isolation — and the first building block of every container.1

3 Building Your First Container

Prerequisites

- A Linux system (I'm using Rocky Linux 9+)

- Root access via

sudo - Basic familiarity with bash and the Linux filesystem

The First Attempt

Let's start simple. Create a directory called my_container and try to chroot into it:

mkdir my_container sudo chroot my_container /bin/bash

chroot: failed to run command '/bin/bash': No such file or directory

This makes sense. When chroot sets my_container as the new root, the path /bin/bash resolves to my_container/bin/bash on the host — and that file doesn't exist yet.

The fix is obvious — we need to create a bin/ directory and copy the bash binary into it:

mkdir -p my_container/bin cp /bin/bash my_container/bin/

Try again:

sudo chroot my_container /bin/bash

bash: error while loading shared libraries: libtinfo.so.6: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

Progress! The binary was found, but now it fails to load. The reason: every dynamically linked binary depends on shared libraries (.so files) at runtime. Without them, the dynamic linker has nothing to work with.

We can use ldd to discover exactly which libraries bash needs:2

ldd /bin/bash

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x......) libtinfo.so.6 => /lib64/libtinfo.so.6 (0x....) libc.so.6 => /lib64/libc.so.6 (0x....) /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x....)

The output shows that bash needs libraries from /lib64/. Let's extract just the paths:

ldd /bin/bash | grep -o '/lib[^ ]*'

/lib64/libtinfo.so.6 /lib64/libc.so.6 /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

Let's create the library directory inside our container and copy these files:

mkdir my_container/lib64 # Copy each library cp /lib64/libtinfo.so.6 my_container/lib64/ cp /lib64/libc.so.6 my_container/lib64/ cp /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 my_container/lib64/

Now try chroot again:

sudo chroot my_container /bin/bash

We're in. This is our first container — primitive, but functional.

bash-5.1# pwd / bash-5.1# cd /bin bash-5.1# pwd /bin bash-5.1# exit

From inside the chroot, / points to my_container/ on the host. We only have bash and its built-in commands (cd, pwd) at this point — no ls, no cat, nothing else. That's expected: if a binary isn't copied into the container, it simply doesn't exist.

4 Building a More Complete Container

The first container proved the concept. Now let's build something we can actually work with.

But before moving foreward, pause and think about what we're really doing here:

the bash process in the previous example is "contained" in the new directory, and to do that we're constructing a minimal Linux filesystem from scratch.

We want the process inside to feel like it's running in a full Linux installation — its own binaries, its own libraries, and eventually its own network stack.

That's what a container fundamentally is: a carefully constructed filesystem combined with isolation mechanisms that control what the process can see, how many resources it can consume, and what privileges it can gain.

For the rest of this series, we'll need a few more tools inside the container:

ls, ps, echo for basic interaction, and nc, ip for the networking parts.

Directory Structure

CONTAINER_ID='my_container' mkdir -p ${CONTAINER_ID}/{bin,sbin,lib,lib64}

Copy the Binaries

# Install netcat if not present sudo dnf install -y nmap-ncat cp -v /bin/{bash,ls,ps,echo,nc} ${CONTAINER_ID}/bin/ cp -v /sbin/ip ${CONTAINER_ID}/sbin/

'/bin/bash' -> 'my_container/bin/bash' '/bin/ls' -> 'my_container/bin/ls' '/bin/ps' -> 'my_container/bin/ps' '/bin/echo' -> 'my_container/bin/echo' '/bin/nc' -> 'my_container/bin/nc' '/sbin/ip' -> 'my_container/sbin/ip'

Copy the Libraries

Each binary has its own set of dependencies. Let's resolve and copy all of them in one pass:

binaries=(/bin/bash /bin/ls /bin/ps /bin/echo /bin/nc /sbin/ip) ldd "${binaries[@]}" \ | grep -o '/lib[^ ]*' \ | while read lib; do [ -f "$lib" ] || continue mkdir -p "${CONTAINER_ID}/$(dirname $lib)" cp -n "$lib" "${CONTAINER_ID}/${lib}" done

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libtinfo.so.6 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libprocps.so.8 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libsystemd.so.0 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libnsl.so.1 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libnss_files.so.2 /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm.so.6 ...

The -n flag tells cp to skip files that already exist — so shared libraries like libc are only copied once, even though multiple binaries depend on them.

Enter the Container

sudo chroot . /bin/bash

bash-5.1# ls / bin lib lib64 sbin bash-5.1# ls /bin bash echo ls nc ps bash-5.1# ls -lh /bin total 7.7M -rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 1.4M Feb 15 10:23 bash -rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 37K Feb 15 10:23 echo -rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 145K Feb 15 10:23 ls -rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 43K Feb 15 10:23 nc -rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 143K Feb 15 10:23 ps bash-5.1# exit

Everything works. The container has an isolated filesystem, functional binaries, and the tools we'll need going forward.

Cool, chroot It's one layer — filesystem isolation. The process inside can still see host processes, share the host network, and consume unlimited resources.

In the next parts, we'll add the missing layers: network namespaces, and resource limits …etc. Each one brings us closer to what docker run actually does.

5 Next in the Series

We'll create network namespaces, wire them together with virtual ethernet pairs,

and test connectivity between containers using the nc and ip tools we just staged.

Footnotes:

chroot changes the filesystem view but is not a security boundary.

A privileged process can escape it.

ldd prints shared library dependencies by inspecting the binary's ELF dynamic section.

On most Linux distributions, it uses the dynamic linker to resolve paths without fully executing the binary.